In the middle of the 1844 presidential election, an explosive story that some believed would transform the campaign appeared in the national media. Instead, it turned out to be a piece of disinformation that proved to be far less consequential than if it had been true.

In the middle of the 1844 presidential election, an explosive story that some believed would transform the campaign appeared in the national media. Instead, it turned out to be a piece of disinformation that proved to be far less consequential than if it had been true.

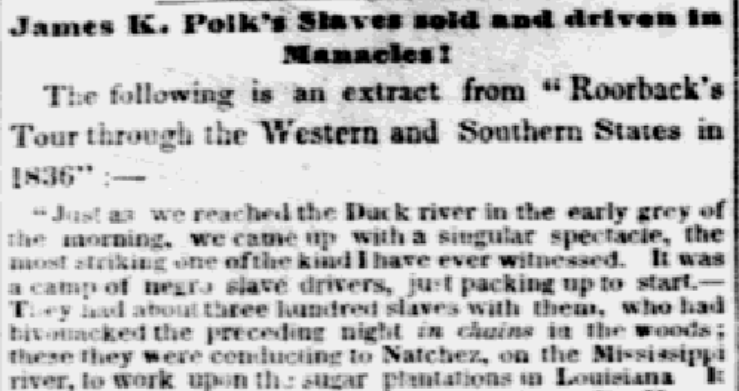

On September 16, the Albany (NY) Evening Journal, an influential Whig newspaper edited by Thurlow Weed and supportive of Henry Clay’s campaign for the White House, reprinted an article from another New York newspaper about an encounter that a German baron named Roorback reportedly had near the Middle Tennessee home of Democratic presidential candidate James K. Polk. According to the account, submitted by a contributor going by the pseudonym “An Abolitionist,” Roorback witnessed a coffle of approximately 300 enslaved people headed to work on Louisiana sugar plantations, with “forty-three of these unfortunate beings” having Polk’s initials branded on their shoulders as a mark of his former ownership of them.

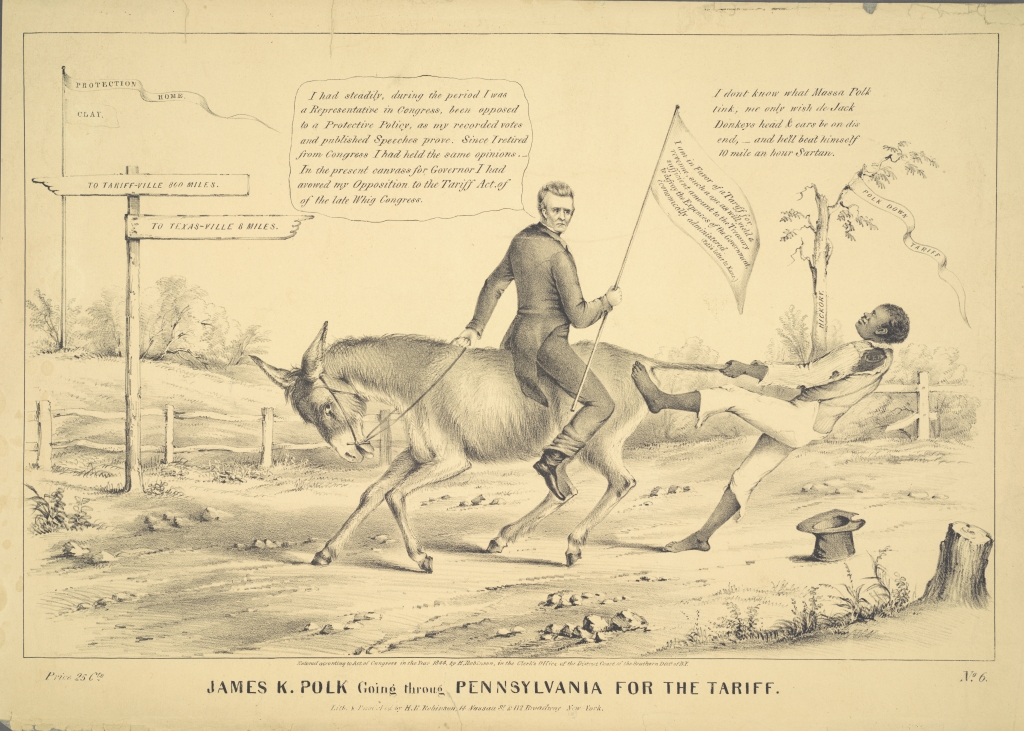

With Weed taking the lead, other Whig editors seized on the story as a definitive reason that voters should support Clay, not Polk, for president. Were voters expected to “elevate to the Presidency a man who sells human beings—men, women and children—to be driven off with chains, WITH HIS NAME BRANDED INTO THEIR FLESH?” Weed asked. “Polk ought to be damned for this cruel deed to perpetual infamy,” the Richmond (VA) Whig pronounced. Even Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren were preferable to “this inhuman coward.” The Whigs went so far as to incorporate the story into a political cartoon. “James K. Polk Going through Pennsylvania for the Tariff” by Henry R. Robinson centered on the Democratic candidate’s views on protective duties, but anyone looking closely at the image could see that the enslaved African American man portrayed in it had “JKP” branded on his arm.

Whigs undoubtedly hoped that focusing attention on Polk’s purported cruelty would accomplish two objectives. First, it would draw attention away from Clay’s identity as an enslaver and his support of the system of inhuman bondage. Before becoming the Whigs’ official nominee, Clay had been confronted at an event in Richmond, Indiana, by abolitionists who petitioned him to free the people whom he had enslaved. Clay responded that while he believed slavery “a great evil,” there were “far greater evils,” such as “a sudden, general, and indiscriminate emancipation” of enslaved people that would lead to “civil war, carnage, pillage, conflagration, devastation, and the ultimate extermination or expulsion of the blacks.” It would be better, he argued, to maintain “the mild and continually improving state of slavery” that existed. Secondly, the Whigs hoped to attract the support of members of the abolitionist Liberty Party, who might decide that voting for the lesser of two slaveholding evils (Clay instead Polk) might be a more pragmatic approach to influence and power than supporting the official Liberty nominee, James G. Birney.

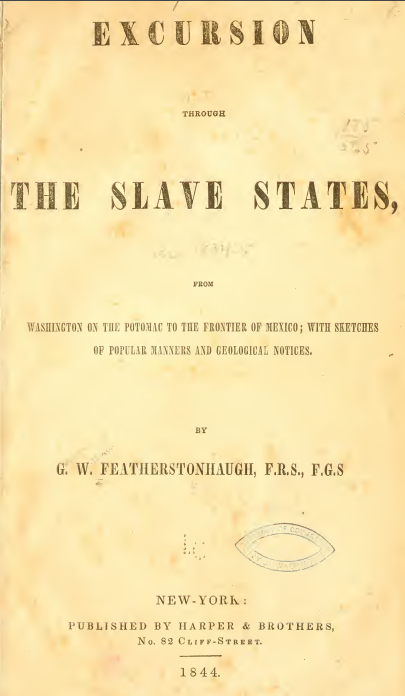

The Whigs’ strategy backfired because, it turned out, the Roorback story was not true. Instead, it was a cannibalized version of George William Featherstonhaugh’s recent publication entitled Excursion Through the Slave States, from Washington on the Potomac to the Frontier of Mexico; with Sketches of Popular Manners and Geological Notices. In the memoir, Featherstonhaugh, the first geologist appointed by the U. S. government, recalled his travels through parts of the South in the mid-1830s. But he did not mention Polk or describe an encounter with African Americans enslaved by the Tennessean.

When it became clear that the Roorback story was a false and manipulated version of Featherstonhaugh’s memoir, Weed and other Whig editors were forced to retract it, opening the door for Democrats to attack their opponents for spreading disinformation. Democrats had proven the story a lie, the party’s vice-presidential nominee George M. Dallas told Polk, “and I think what was intended to injure you will yet be made the means of extensive benefit.” “The ‘Roorback’ forgery & falsehood, is the grossest & basest I have ever known,” Polk pronounced. “It is in all its facts an infamous falsehood. I am glad the Democratic press, at the East, have been able so promptly to meet and expose it.”

When it became clear that the Roorback story was a false and manipulated version of Featherstonhaugh’s memoir, Weed and other Whig editors were forced to retract it, opening the door for Democrats to attack their opponents for spreading disinformation. Democrats had proven the story a lie, the party’s vice-presidential nominee George M. Dallas told Polk, “and I think what was intended to injure you will yet be made the means of extensive benefit.” “The ‘Roorback’ forgery & falsehood, is the grossest & basest I have ever known,” Polk pronounced. “It is in all its facts an infamous falsehood. I am glad the Democratic press, at the East, have been able so promptly to meet and expose it.”

One of the ironies of the “Roorback hoax,” as it came to be called, was that if Whigs had done their due diligence and dug a little deeper into Polk’s slaveholdings, they might have uncovered evidence to support their claim that the Democratic nominee was a violent enslaver. Polk owned nearly forty enslaved African Americans in 1844, with most of them laboring on his plantation in Yalobusha County, Mississippi. Like many absentee enslavers, Polk relied on overseers and male relatives to run day-to-day operations and, as in many such arrangements, the enslaved people sometimes found themselves whipped or sold for not acquiescing to the enslaver’s power. While many southern voters would have understood, accepted, and even approved of Polk’s status as an enslaver, to win the presidency, he still had to appeal to voters outside of the region, many of whom might have been uncomfortable with his ownership and treatment of enslaved people.

But the Whigs missed their opportunity, and Polk went on to defeat Clay later that fall. Did the Roorback story make a difference? It’s impossible to say with certainty, but in an extremely close election–one that Polk won by approximately 40,000 popular votes–every vote mattered.

Sources:

Mark R. Cheathem, Who Is James K. Polk? The Presidential Election of 1844 (Univ. Press of Kansas, 2023).

James L. Rogers II, “The Roorback Hoax: A Curious Incident in the Election of 1844,” Annotation 30 (September 2002): 16-17.